ANZAC Hero – Not Recognised

July 6, 1892 – May 19, 1915

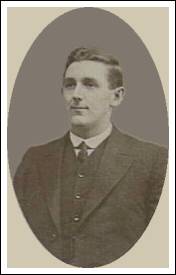

A 1913 portrait photo of Simpson, Aged 21.

(AWM A02826)

John Simpson Kirkpatrick, affectionately known as “the man and his donkey”, was born on the 6th of July 1892 in South Shields, England.

He landed at ANZAC Cove at 5 a.m. on the 25th of April 1915 and was mortally wounded in Shrapnel Gully, near the mouth of Monash Valley, on the 19th of May 1915 at the age of 22.

During the 24 days he spent at ANZAC he operated as a sole unit with his beloved donkey/s and is credited with saving the lives of probably hundreds of men.

He has become a part of the ANZAC folklore and though recommended for the Victoria Cross, twice, and the Distinguished Conduct Medal, he was never decorated for his actions.

Early life

His parents, Robert and Sarah, were Scottish. Robert was a merchant seaman for 20 years before finally settling at South Shields, Tyneside.

Each summer young John worked at Murphy’s Fair, providing donkey rides for the children for a penny a ride. John, known commonly as Jack, looked after the donkeys from 7.30 a.m. to 9.00 p.m. when he would ride one the 2 miles to his home. The animals responded well to his gentle, kind manner, he seemed to have an instinctive attachment with them.

A serious accident in 1904 left his father, Robert, incapacitated and he died in 1909. After his father’s accident, young Jack took on a series of jobs to help support the family.

At age 17 years and 3 months, 2 days after the death of his father, he, like his father, answered the call of the sea and sailed from Tyne on the “SS Heighington”. He spent the next 3 months on the Mediterranean run before returning home for Christmas in 1909.

On February 12, 1910, he joined the crew of the “Yedda” as a stoker and sailed for Newcastle, Australia. On arrival in Australia he and a dozen of the crew “cleared out”. For the next few years Jack worked a series of jobs in different parts of the country, cane cutting, cattle droving, coal mining, “humping the bluey” (better know nowadays as back-packing!), working at the gold fields and working on coastal ships.

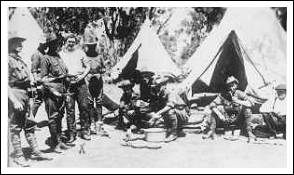

Left to right: Pte A.J. Currie, Lance Corporal A.J. Davidson Pte W. Lindsay, Pte John Simpson, Pte F.J. Kennedy, Driver C. Mansfield, Pte E.L. Langoulant, Pte F.E. Meacham Pte J.C. Dinsdale, Unknown.

(AWM A02827)

On the 25th of August, 1914, at the age of 22 years and 1 month, Simpson jumped ship from the “SS Yankalilla” in Fremantle, Western Australia, and enlisted in Perth just 3 weeks after the outbreak of World War 1.

Prior to joining up he dropped Kirkpatrick from his name and took on Simpson as his surname possible because a deserter from the Merchant Marines may not be accepted into the army.

Simpson, a big strong lad, was allotted to the Field Ambulance as a stretcher bearer.

Simpson had hoped that, by joining the army, he might get a free trip back home to England which was where the initial Australian force were destined to go for their basic training. They were diverted to Egypt when it was realised that England wasn’t prepared for this large colonial force.

Exactly 8 months after enlisting Simpson landed at ANZAC Cove, Gallipoli, as a stretcher bearer, with “C” section, 3rd Field Ambulance, 1st Australian Division, Australian Imperial Force.

The first 24 hours at ANZAC

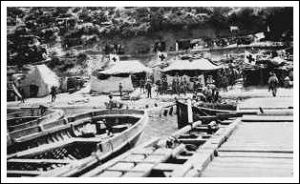

“C” section rowed ashore from the transport “Devanha”. Just before dawn, at about 5.00 a.m. on Sunday April the 25th 1915, they leapt from the boat and waded ashore.

Simpson was the second man in the water. The first and third men were killed. Casualties on the first day were appalling. Of the 1500 men in the first wave, 755 remained in active service at the end of the day. The remainder were killed or wounded. Those that did remain were badly affected by the shortage of food and particularly water in the sub-tropical sun.1

There was also a shortage of stretchers, medical equipment and supplies. Stretcher parties were reduced from 6 men to 2. They improvised as best they could and worked all day tending to the wounded and carrying them down to the Casualty Clearing Stations on the beach at ANZAC Cove.

A primitive collecting post was established using the cover of the overgrown vegetation beyond the beach. Capt. Douglas McWhae of ‘C’ Section wrote of the landings

“The Red-Cross flag was put up after a time. The three sections were going for all they were worth… they had iodine and field dressings; all splints were improvised using rifles and bushes. They were terrible wounds to deal with.”

By dawn on the second day the ANZAC’s were holding onto a 500 acre piece of ground. The Turks held the high ground and looked down into the ANZAC position at almost every angle. Stretcher parties were under constant rifle and artillery fire.

Simpson finds a donkey

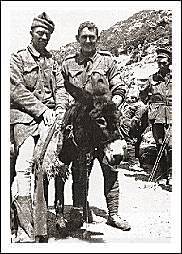

Helping a soldier wounded in the leg. (AWM J06392)

Several donkeys were landed and some had been abandoned and were grazing in the wild overgrown gullies. Simpson, having already carried two heavy men down from the front lines, responded to a call from a wounded man. He had by this time been reported missing, saw a donkey grazing nearby and decided to use the donkey to help carry him to the beach.

The donkey responded to the sure touch of the friendly man with the experience gained at Murphys Fair as a young man back in South Shields.

There was no saddle, stirrups or reins. Simpson made a head stall and lead from bandages and field dressings for this first trip. He lifted the wounded man onto the donkey and held onto him as he guided the donkey to the beach.

From this day on Simpson decided to act as an independent unit. He did not report back to ambulance headquarters for instructions and for the first 4 days was technically a deserter until his CO (Commanding Officer), seeing the value of his work, agreed to turn a blind eye and approved his actions.

Later he made a saddle from bags and blankets and used ropes for the head stall and lead. Some of his friends made a small bell from the nose cone of a shell.

The daily routine

Simpson and his donkey would make their way up Shrapnel Gully, the main supply route to the front line, into Monash Valley and onto the deadly zone around Quinn’s Post where the opposing trenches were just 15 yards apart.

To the left of Quinn’s Post was Dead Man’s Ridge, held by the Turks. From here they were able to snipe right down Shrapnel Gully.

(AWM A03114)

Simpson would start his day as early as 6.30 a.m. and often continue until as late as 3.00 a.m. He made the one and a half mile trip, through sniper fire and shrapnel, 12-15 times a day. He would leave his donkey under cover, whilst he went forward to collect the injured. On the return journey he would bring water for the wounded.

He never hesitated or stopped, even under the most furious shrapnel fire and was frequently warned of the dangers ahead but invariably replied “my troubles”.

It is unclear whether he used one donkey or several though we do know that he used several names, “Murphy”, “Abdul”, his favourite “Duffy” and even “Queen Elizabeth”. He certainly only used one donkey at a time as the terrain was too restrictive to use more.

The need for fodder led him to the only source, which was at the foot of Shrapnel Gully, in the form of the 21st Kohat Indian Mountain Artillery Battery2. The Indians had brought mules to haul their artillery and had brought plenty of fodder. Simpson set up camp with them, slept and ate with them and was idolised by them. The Indians called him “Bahadur” which means “the bravest of the brave”. To the other troops he was known as “Scotty”, “Murphy”, “Simmie”, and generally “the man with the donk”.

General C. H. Brand3 described Simpson with his donkey as he was often seen.

Almost every digger knew about him. The question was often asked : “Has the bloke with the donk stopped one yet?” It seemed incredible that anyone could make that trip up and down Monash Valley without being hit. Simpson escaped death so many times the he was completely fatalistic. He seemed to have a charmed life.

Simpson the man

The Australian Dictionary of Biography records Simpson as “a typical digger; independent, witty, warm-hearted, happy to be indolent at times and careless of dress.”

Army records describe Private Simpson J, number 202, of fair complexion, brown hair, blue eyes, 5 ft 8 in tall, 12 stone and of solid build.

His friend Andy Davidson described him as

“a big man and very muscular, though aged only 22 and was selected at once as a stretcher bearer… he was too human to be a parade ground soldier, and strongly disliked discipline; though not lazy he shirked the drudgery of ‘forming fours’, and other irksome military tasks” and “he was very witty, and inclined to the lazy, very popular, liked a pot or two but did not drink to excess, careless of dress and was a handful to Sgt. Hookway, his Section Sergeant.”

Simpson had a strong sense of humour, of devilment and a sheer exuberant enjoyment of life. He would quickly become popular with virtually anyone with whom he came in contact.

C.1914-09. (AWM A03116)

F. W. Dyke, a Gallipoli original, recalled a rare occasion when his donkey was being obstinate. A Padre was standing waiting to accompany Simpson, but with all his coaxing the donkey wouldn’t move. At last Simpson turned to the Padre and said,

“Padre, this old donkey has been tied up with some mules and has acquired some of their bad habits. Would you move along the beach a little way, as I’ll have to speak to him in Hindustani, and, Padre, I wouldn’t like you to think I was swearing at him.”

On another occasion he saw a figure moving in the bush and shouted, “Halt! there, who are ye?”

“I’m a warrant officer of the 3rd Field Engineers” came the response.

“Come out, then, and let’s have a look at ye” replied Simpson.

He examined the suspect and said bluntly “I don’t like the looks of ye.”

The warrant officer stared and said, “Don’t be foolish. I’ll report you. I’m making levels for the excavations for a new road here.”

“Maybe, maybe, but ye’ll come down to the station with me all the same”

Upon arrival there, the warrant officer was identified.

Simpson commented, “Oh well, ” flicking the donkey as he spoke, “he’s dirty enough to be a Turk even if he ain’t one, isn’t he, Duffy?”

On May the 15th General Bridges set out on his daily excursion to see his men, accompanied by Colonel C.B.B. White and Lieutenant R.G. Casey4. They took their way into Shrapnel Gully and on through Monash Valley. Bridges stopped to talk to the medical officer at the aid post. When he moved on he was mortally wounded. Lieutenant Casey recalled how Simpson came up to the dressing station soon after with his donkey.

Simpson made a friendly remark, “You’ll be all right, Dig. I wish they’d let me take you down to the beach on my donkey.”

Bridges had earlier told Captain Clive Thompson “Don’t have me carried down. I don’t want to endanger any of your stretcher-bearers.”

Simpson was frequently warned of the dangers he was facing. When Captain A. Lyle Buchanan took over as Simpson’s commanding officer he officially warned Simpson of the grave risks he was taking as the possible consequences of wounding “or worse”. Simpson’s reply was “my troubles” and he continued on with his work.

As E.C. Buley tells in his book ‘Glorious Deed of Australia in the Great War’, he sometimes even acted against orders.

When the enfilading fire down the valley was at its worst and orders were posted that the ambulance men must not go out, the Man and the Donkey continued placidly their work. At times they held trenches of hundreds of men spell-bound, just to see them at their work.

Their quarry lay motionless in an open patch, in easy range of a dozen Turkish rifles. Patiently the little donkey waited under cover, while the man crawled through the thick scrub until he was within striking distance. Then a lightning dash, and he had the wounded man on his back and was making for cover again. In those fierce seconds he always seemed to bear a charmed life.

One of the several men that Simpson helped, P.G. Menhennett said,

Two or Three times on the way down he grinned at me and said “That was a very nasty spot we have just passed. Jacko’s snipers are wonderful shots. It doesn’t do to loiter in such spots.”

When you realise that he knew the extreme danger to which he so constantly exposed himself in his self-imposed errands of mercy you can only marvel at the cheerful way in which he carried out his duties. He brought me safely to the Beach clearing station and when I thanked him he smiled and said “Glad to help you”.

However, when an officer that he had brought down to the beach offered him a gold sovereign he said

“Keep your blinking quid. I’m not doing this for the money.”

Capt. Victor Conrick, winner of the DSO (Distinguished Service Order) and Mentioned in Despatches three times for bravery, passed Jack one day in Monash Valley and called out to him – “Look out for yourself Simmy.” Jack’s laughing reply came, “That bullet hasn’t been made for me yet sir.” Conrick added, “Simpson was a very game man and in fact laughed at danger. At all times he was very cheerful and a very great favourite with his mates of 3 Field Ambulance. Simpson carried out a very dangerous mission. He had several donkeys killed while on his job.”

His last day

On May 19th 1915, at 3.00 a.m.,the Turks mounted a major counter-offensive. 45,000 Turkish troops attacked all along the front line with orders to drive the enemy into the sea.

By 11.00 a.m., 8,000 Turks lay dead and wounded in no-man’s land without capturing a single section of trench. The great assault had finished and failed. The attack was called off.

It was during the final fling of the attack that Simpson made his way up the gully towards Courtney’s Post where the fighting had been most furious. It was his habit to stop at the water guard and have breakfast. On this day he was too early and breakfast wasn’t ready. “Never mind,” said Simpson as he continued on his way “get me a good dinner when I come back.”

He picked up a wounded man, placed him on the donkey, Duffy, and made his way towards the beach. On his way he passed and chatted briefly with Private Langoulant, Lance Corporal Andy Davidson (both friends from Blackboy Hill training camp) and Private Mahoney, who had been in charge of the boat they landed in.

It was as he reached the very spot where General Bridges has been hit a four days before that Signaller D.M. Benson, who was dug in beside the track, shouted to him “Watch out for that machine gunner. He’s got a couple of blokes this morning already.” Simpson waved back in acknowledgement and, grinning, continued on his way.

Moments later the Turkish machine gun opened fire. Simpson was hit in the back. The bullet passed out the front of his stomach killing him instantly. The force of the bullet picked him up and threw him face down in the dirt. Davidson, Mahoney and Langoulant amongst others ran back to Simpson but it was too late.

The wounded man on the donkey was wounded a second time and as he grasped the donkey’s neck, he passed out. The donkey, frightened, and still with the wounded man on his back ran down to his usual destination, No.2 Dressing Dugout.

(AWM C02207)

There, Padre C.J. Bush-King, helped lift the wounded man from the donkey. He recalled “I turned the donk around. I slapped its rump. It slowly moved off from whence it came, I followed. Moving slowly, the donk browsed what rough feed he could, and went along the track made familiar by use. When we came to the most dangerous place, Simpson’s body lay there.”

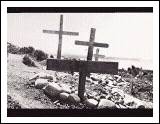

Davidson said, “We covered his body and put it in a dugout beside the track and carried on with our job. We went back for him at about 6.30 p.m. and he was buried at Hell Spit5 on the same evening.” Private Johnson made a simple wooden cross with the inscription “John Simpson”.

Chaplin-Colonel George Green (Church of England) officiated at the burial service.

One of the 1st Battalion missed him from the gully that day and asked “Where’s Murphy?” The Sergeant replied “Murphy’s at Heaven’s Gate, helping the soldiers through.”

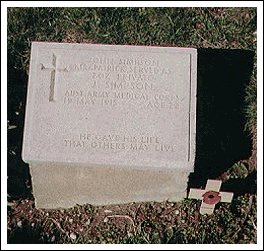

After the armistice a commemoration stone replaced the cross. The inscription reads:

JOHN SIMPSON

KIRKPATRICK SERVED AS

202 PRIVATE J SIMPSON,

AUST. ARMY MEDICAL CORPS,

19TH MAY 1915 – AGE 22

HE GAVE HIS LIFE

THAT OTHERS MAY LIVE.

That night there was a hush throughout the trenches when the news circulated that “the man with the donk” had finally “stopped one”. He had become such a part of life at ANZAC that it was hard for them to believe that he was gone.

Sapper Burrell told that when Simpson was shot, an artilleryman told Captain J.T. Evans, the Officer commanding the Indian Field ambulance, “Evans Sahib, what do you think? Murphy’s stonkered.” Evans did a thing which astonished all who knew him. He sat on a packing case and covered his face with his hands and prayed out aloud. “O God. if ever a man deserves Heaven, he does. Give it to him!”

The Indians gathered around and asked Evans what was wrong and when he told them Murphy Sahib had been killed they immediately went down on their haunches and wailed and threw dirt on their heads. “I never seen them show such sorrow for one of their own.” Sapper Burrell said.

![]()

No Decoration

Although he only spent 4 years in Australia, Simpson embodied that larrikin character, that inability to respect for the sake of respect, that dislike of authority that has come to be known as the ANZAC spirit.

Unfortunately the authorities at the time didn’t have the same admiration for this spirit that we have. And though Simpson was nominated several times to be decorated for his bravery, these nominations were declined.

It is apparent that all who saw his work felt he was deserving of the highest awards.

Sergeant J.E. McPhee, 4th Field Ambulance, recorded in his personal diary on May 10th, 1915:

“Simpson … doing great work, bringing wounded from the trenches, dressing stations etc. on a little donkey .. Deserves V.C.. During the first push he brought a couple of men from beyond the firing line. Works by himself.”

Padre George Green, who lead Simpson’s burial service, later said :

“If ever there a man deserve the Victoria Cross it was Simpson. I often remember now the scene I saw frequently in Shrapnel Gully of that cheerful soul calmly walking down the gully with a Red Cross armlet tied round the donkey’s head. That gully was under direct fire from the enemy almost all the time.”

The official Australian War Historian, C.E.W. Bean6 wrote:

“Simpson escaped death so many times that he was completely fatalistic; the deadly sniping down the valley and the most furious shrapnel fire never stopped him… He carried many scores of men down the valley, and had saved many lives, at the cost of his own.”

Colonel Monash7 fully recognised the value of Jack’s self-imposed role, stating that “Simpson was worth a hundred men to me.”

Jack was recommended for the Victoria Cross, officially, through his unit, on June 3rd 1915. He was also recommended for the highest military honours by Colonel Monash. Monash, commander of the 4th Brigade at the time (where Jack was operating) an eye-witness to his activities sent in a lengthy submission to Australian and New Zealand Divisional Headquarters on May 20th, the day after Jack had been killed.

I desire to bring under special notice, for favour of transmission to the proper authority, the case of Private Simpson, stated to belong to C Section of the 3rd Field Ambulance. This man has been working in this valley since 26th April, in collecting wounded, and carrying them to dressing stations. He had a small donkey which he used, to carry all cases unable to walk.

Private Simpson and his little beast earned the admiration of everyone at the upper end of the valley. They worked all day and night throughout the whole period since the landing, and the help rendered to the wounded was invaluable. Simpson knew no fear and moved unconcernedly amid shrapnel and rifle fire, steadily carrying out his self-imposed task day by day, and he frequently earned the applause of the personnel for his many fearless rescues of wounded men from areas subject to rifle and shrapnel fire.

After Simpson’s death Lt-Col. Sutton wrote in his diary:

May 19 – “Attended funeral of poor Simpson.”

May 24 – “I sent in a report about No. 202 Pte. Simpson J., of C Section, shot on duty May 19th.

He was a splendid fellow and went up the gullies day and night bringing down the wounded on donkeys. I hope he will be awarded the D.C.M.” (Distinguished Conduct Medal)

June 1st – “I think we will get a V.C. for poor Simpson.”

June 4th – “I have been writing up poor Simpson’s case with a view to getting some honour for him. It is difficult to get evidence of any one act to justify the V.C. the fact is he did so many.”

There is a clue here to one of the reasons that has been proposed, why Simpson may not have been awarded the V.C. In 1915, the Victoria Cross was awarded for “some signal act of valour, or devotion to country, in the presence of the enemy.” Note the use of the word “signal”. [Oxford Dictionary: Signal: a,n,v. 1. of marked quality or importance.] As the above diary entry suggests it seems that there may have been some confusion as those that were nominating him were looking for a single (“any one act to justify the V.C.”) act.

It has also been suggested that stretcher bearers weren’t eligible as it was part of their normal duty. Colonel Neville Howse VC, commander of the Australian Medical Corps, is alleged to have stated openly that no other of the medical corps would win the award whilst he is alive. Howse won his VC in the Boer War. Howse is the only member of an Australian medical unit to receive the Victoria Cross.

But it was not until August 1916, 15 months after Simpson was killed, that the British High Command issued an official directive to this effect. Furthermore, a British stretcher bearer, Lance Corporal W.R. Parker, won the Victoria Cross at Gallipoli on May 1st, 1915, for helping rescue wounded men, though wounded himself.

In July 1967 a second unsuccessful attempt was made to earn Simpson his well-deserved Victoria Cross. The Prime Minister, Harold Holt, the Governor-General, Lord Casey 4, the Chief of the General Staff, Major General Brand3, and others sent a petition to the British War Office on behalf of the people of Australia, requesting that the Victoria Cross be awarded to Simpson. The request was denied on the basis that “It would begin a precedent which would be impossible to implement.” In fact the precedent to make an extremely late award had already been set when in 1907, the V.C. was awarded, posthumously, to two Lieutenants, Lieutenants Melvill and Coghill, for their gallant actions during the Zulu Wars, in 1879, 28 years earlier.

The Cross Of Valour. On February 14th 1975, five awards, recognising acts of bravery, were instituted into the Australian honours and awards system.

The “Cross of Valour” being the highest of these and is outranked only by the Victoria Cross.

On August 15th 1995 the Echuca-Moama R.S.L. nominated John Simpson for this decoration. The nomination failed due to technical reasons.

Current and on-going

NSW Labor MP Jill Hall currently has a private members bill before the the Australian parliament.

Jill Hall’s proposes “that this House remembers the extraordinary deeds of John Simpson Kirkpatrick [and his donkey] … 2. implores the Government to award a posthumous Victoria Cross of Australia to ‘Simpson’ in accordance with the wishes of his commanding officers and overwhelming public demand.”

For a report on her progress read Sydney Morning Herald article 01/11/2000 –

Honour for the man with the donkey long overdue

To add your name to the ever growing petition visit the John Simpson page at John Woods ANZACs site.

The Victoria Cross for Australia was established on 15 Jan 1991 as the highest Australian operational gallantry award. It supersedes the Victoria Cross instituted by Queen Victoria in 1856 but is physically identical. Now three Victoria Cross for Australia have been awarded.

The Victoria Cross for Australia shall only be awarded for the most conspicuous gallantry or a daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice or extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy. Subsequent awards to the same person will be made in the form of a Bar. It may be awarded posthumously.

In 1965 these stamps where issued, in Australia, depicting Simpson and his donkey with a wounded soldier, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the ANZAC landings.

In 1965 these stamps where issued, in Australia, depicting Simpson and his donkey with a wounded soldier, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the ANZAC landings.

The design, featuring Simpson and his donkey, was prepared by Cari Andrew, who based his sketch on the Simpson statue by Wallace Anderson at the Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne. The colours were specially chosen to emphasise aspects of the Gallipoli campaign. The khaki and blue recall the parts played by Army and Navy units and maroon, the colour of the Victoria Cross, symbolises sacrifice and heroism.

Similar stamps were issued also in 1965 in the Australian Protectorate Islands.

In 1995 this Australian five dollar commemorative coin was released again depicting Simpson and his donkey with a wounded soldier.

In 1995 this Australian five dollar commemorative coin was released again depicting Simpson and his donkey with a wounded soldier.

No campaign medal was ever struck for the Gallipoli campaign.

In 1967 the Australian Government struck this medallion, the ANZAC Commemorative Medallion, which depicts Simpson and his donkey. Simpson was awarded medal No. 1

Every Anzac soldier who served on the Gallipoli Peninsula, or in direct support of operations there – or his family if he did not survive until into the late 1960s – was entitled to be issued with the ANZAC Commemorative Medallion.

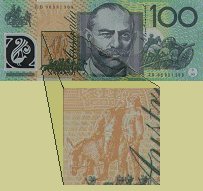

Simpson’s image on the Australian 100 dollar note, which depicts General Sir John Monash.7

——————————————————————————–

Appendix

1. The high command had never expected to be held up on the beach with such high casualties and therefore hadn’t planned for the necessary water and provisions to be available. They expected to sweep across the peninsula with very few casualties, capturing water sources along the way.

2. The Indians weren’t used in their usual role as it was suspected that they wouldn’t fight against their fellow Muslims and so they were deployed using their mules to cart water and supplies to the front lines.

3. General C. H. Brand later Chief of the General Staff Australian Army.

4. Lieutenant R.G. Casey went on to become Lord Casey, Governor-General of Australia.

5. Hell Spit is the southern point of ANZAC Cove and the cemetery there is now known as ‘Beach Cemetery’.

6. Charles Bean, later Dr., wrote the 13 volume official history of Australia in the first world war. He also was the driving force in the creation of and founder of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

7. Colonel Monash, later General Sir John, went on to become Australia’s greatest commander of the First World War.

By recognising the value of the newly invented tank and by introducing detailed planning prior to each battle he changed the face of warfare from one of frontal assaults at heavy cost to one of science.

Monash University in Melbourne is named after him and he is featured on the Australian 100 dollar